Modern physics

Key points: Four fundamental forces;

fundamental particles; matter and antimatter

| There are four fundamental forces - they account for all forces known

to physics. We have already met three of them: 1.)

Gravitational (very, very weak)

2.) Electromagnetic (moderate)

3.) Nuclear (very strong)

In addition, there is 4.) the "weak"

nuclear force that is required to explain some nuclear reactions. (illustration

from CERN) |

|

Although gravity is very, very weak, it has the advantage that it acts at long

range, and that there is only one sign for the force - unlike electric charges, there are

no plus and minus gravity charges to cancel each other out. Thus, gravity is the dominant

force over distances of a few kilometers and greater.

The electric force is an inverse r squared force, just like gravity, and it is

much stronger. However, it is canceled out over large distances by the existence of plus

and minus charges - if there is enough charge of one sign to exert a long-range force, the

first thing it does is attract particles with the opposite charge, and they cancel much of

the force. Nonetheless, it is generally dominant over distances from the separation of the

proton and electron in an atom, about 10-13 kilometers = 10-10

meters, up to a few kilometers.

| The nuclear forces are short range, and act over the size of an

atomic nucleus only, about 10-13 meters. To the right is an artist's concept of

the strong nuclear force bonding the protons and neutrons in an atomic nucleus. (from

Judy Racz, http://home.vicnet.net.au/~richard/racz.htm) |

|

Nuclear Particles

Modern physics has discovered far more particles than just the photon, proton,

neutron, and electron that we have discussed We will learn a bit more about quarks and the early Universe soon.

They are thought to be the basic building blocks for all matter

We will learn a bit more about quarks and the early Universe soon.

They are thought to be the basic building blocks for all matter There are six of them, and

physicists with some measure of whimsy have named them up, down, top, bottom, strange, and

charm. They have fractional electric charge (either +2/3 or -1/3), and in various

combinations account for some 200 separate larger particles. They are held in these

various combinations by the strong nuclear force, and in fact are highly unstable unless

confined this way. As an example, the proton is made of two "up" quarks, each

with charge of +2/3, and one "down" quark, with a charge of -1/3. Neutrons are

one "up" quark and two "down quarks. If quarks are so unstable, how to we

know they are real? Well, the theory based on them has many successes in explaining the

behavior of nuclear particles, in a simple and unifying way, so we accept both the theory

and the reality of quarks.

There are six of them, and

physicists with some measure of whimsy have named them up, down, top, bottom, strange, and

charm. They have fractional electric charge (either +2/3 or -1/3), and in various

combinations account for some 200 separate larger particles. They are held in these

various combinations by the strong nuclear force, and in fact are highly unstable unless

confined this way. As an example, the proton is made of two "up" quarks, each

with charge of +2/3, and one "down" quark, with a charge of -1/3. Neutrons are

one "up" quark and two "down quarks. If quarks are so unstable, how to we

know they are real? Well, the theory based on them has many successes in explaining the

behavior of nuclear particles, in a simple and unifying way, so we accept both the theory

and the reality of quarks.

Another particle is the neutrino. It is the product of certain reactions we will

learn about when we study the energy output of the sun, for example. Neutrinos have little

or no mass and hence travel at virtually the speed of light. They almost do not react at

all with other forms of matter, so they can escape from the very core of the sun and make

it to earth.

Matter and Antimatter

Einstein's E = mc2 implies that it might be possible for nuclear

particles to get converted to energy, and energy to nuclear particles. And so it is.

However, understanding how it happens leads to a new perspective on matter. It shows that

there is a whole zoo of nuclear particles just like the ones we have discussed except

reversed in key aspects, such as electric charge. Thus, there is an anti-proton, with the

same mass as a proton but negative charge. There is an anti-electron (sometimes called a

positron), with the same mass as an electron but a positive charge, and so forth.

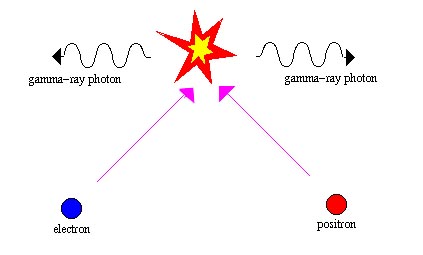

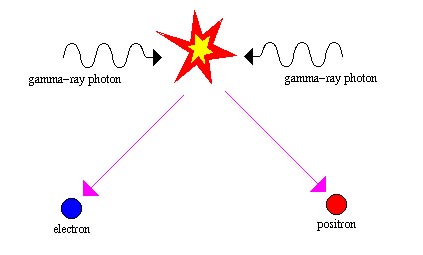

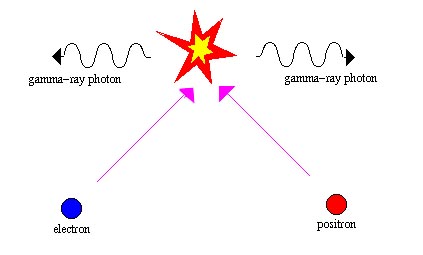

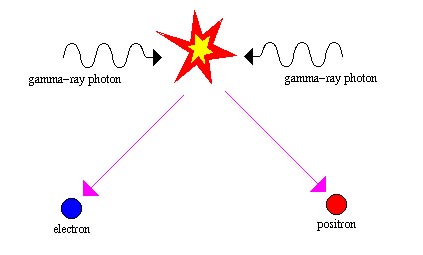

| When a particle encounters its anti-particle, they

annihilate each other and the energy predicted by Einstein's equation emerges as two gamma

rays. Similarly, if gamma rays come together in just the right way, they can disappear

with the creation of a particle and its anti-particle. (figures

from J. Schombert, http://zebu.uoregon.edu/~js/ast123/lectures/lec18.html) |

|

|

Rainbow, from http://www.lioncrusher.com/ecard/ |

|

J. Hevelius at the telescope |

Click to return to syllabus |

| Click to return to Spectroscopy |

hypertext  G. H. Rieke G. H. Rieke |

Click to go to Observatories |