Key points: wave-particle duality; interference; temperature; inverse r squared law; luminosity; the electromagnetic spectrum

is a form of electromagnetic radiation, vibrating electric and

magnetic fields moving through space. The Greek letter lambda (![]() )

is used for the distance between crests, or the "wavelength".

)

is used for the distance between crests, or the "wavelength".

(From Nick Strobel Go to his site at www.astronomynotes.com for the updated and corrected version.)

Light is also a form of fundamental particle, called a photon. That is,

Light has "wave-particle duality"

1. Interference

|

Many experiments show that light interferes with itself, a general property of waves. Here is an example with water waves, created at two spots. The picture shows how they add and subtract to create a complex pattern of ripples.This process is interference. To the right, an animation shows how the pattern changes as the distance between the two spots decreases. from U. Colorado, http://www.colorado.edu/physics/2000/schroedinger & Multimedia Physics, http://www.glenbrook.k12.il.us/gbssci/phys/mmedia/waves/ipd.html |  |

|

How interference works: the black wave is the sum of the blue and brown ones. When the blue one is "in phase" with the brown, they interfere constructively and the black one is larger than either. When the blue one is "out of phase", they interfere destructively and cancel each other out; the black wave vanishes. (animation by G. Rieke). |

|

Rather than drawing the curvy lines for a wave, sometimes we just draw a straight line for the wave crest seen from the top. |

|

Here is how the interference animation transfers to this version. (by G. Rieke). |

We will show the kind of experiment used to see light interference after the discussion of diffraction and particle behavior.

2. Diffraction

|

When light encounters a barrier, such as a slit, its path bends and

it can illuminate areas behind the slit that are larger than the width of the slit. Here

are water waves at a breakwater (to left, from J. Alward,) and diffraction in action to right.(animation by G. Rieke) |

|

1. Discrete energies

Photons have specific, discrete energies.

2. Isolated arrival times

| Here is a movie of a comet, taken with a device that amplifies low

light levels and shows every photon. Note the grainy appearance, due to the detection of

individual photons from the sky. This appearance results directly from the discrete energy

and isolated arrival times of the photons. from Peter McCullough, http://www.astro.uiuc.edu/~pmcc/comet/pinhole.html |

|

Wave-Particle Duality:

If we shine photons one at a time into the box below, we will detect them as discrete particles, each one at a specific position against the back surface. However, if we collect a large number of photons, they will distribute themselves in the "dark" areas and avoid the "light" ones. The "dark" areas are where the positive wavefronts overlap from the two slits letting each photon through. Thus, they result from the combination of diffraction and interference. Perhaps the most curious part is that each photon must pass through both slits! This experiment is called "Young's fringes" after the first scientist to do it.

|

|

If you find this experiment troublesome -- well, so does everyone else![]()

With changing wavelength, short wavelength to long wavelength, we go from: gamma-rays => x-rays => ultraviolet => visible => infrared => microwave => radio (A nanometer = nm is 10-9 m) (From Hopkins Ultraviolet Telescope Project, http://praxis.pha.jhu.edu/.) |

|

These are all forms of “light” or electromagnetic radiation.

The speed of light, c, is a universal constant

c = 3 x 108 meters/sec or c = 3 x 105 kilometers/sec

c = ![]() times

times ![]()

where ![]() is wavelength and

is wavelength and ![]() is frequency. The frequency is the number of wave

crests that pass by a given fixed point per second. From this equation, if we know the

wavelength we can compute the frequency, or if we know the frequency we can compute the

wavelength.

is frequency. The frequency is the number of wave

crests that pass by a given fixed point per second. From this equation, if we know the

wavelength we can compute the frequency, or if we know the frequency we can compute the

wavelength.

We call a particle of light a photon, so it travels at speed c, obeys the above relationship between wavelength and frequency and it also follows this relation:

E = h times ![]()

where E is energy, h is a constant called Planck’s constant and ![]() is frequency.

Thus, if we know the wavelength or frequency, we can compute the energy.

is frequency.

Thus, if we know the wavelength or frequency, we can compute the energy.

The "Kelvin" temperature scale sets 0 at the lowest possible temperature, where the atomic motions are "stopped" (to the limits set by quantum mechanics). The speed of motion of molecules is proportional to the square root of T(Kelvin) divided by the mass of the molecules.

|

We compare hydrogen (yellow, mass = 2) with oxygen (blue, mass = 32) to the left. As the temperature goes up, the speed of the molecules increases (especially for the low mass ones) and their force on the container walls (the pressure) also increases. (animation by G. Rieke) |

Examples: 0o Kelvin = -459o F;

273o K = 32o F = 0o C

Note that Centigrade (or Celsius) degrees are the same size as Kelvin degrees.

Fahrenheit degrees are only 5/9ths as large.

|

As objects get hotter, they emit more

and at shorter wavelengths. (animation

by G. Rieke) The curves as shown to the left are

called blackbody curves – they represent the distribution over wavelength of

the energy emitted by a hot object whose surface would appear perfectly black if it were

cool. Many astronomical objects radiate energy almost as though they were blackbodies. We now discuss the basic "radiation laws" that describe te behavior of blackbody radiators in physical terms: |

|

Stefan-Boltzmann Law: the total energy emitted by a blackbody E = |

|

The curve has the same shape regardless of temperature, and its peak gets shorter in wavelength as 1/T Wien Displacement Law:

|

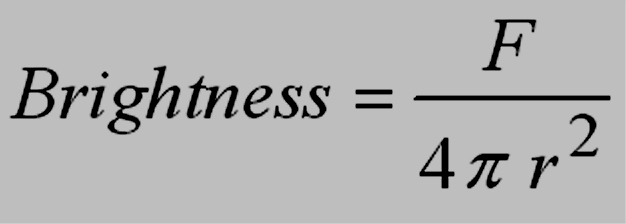

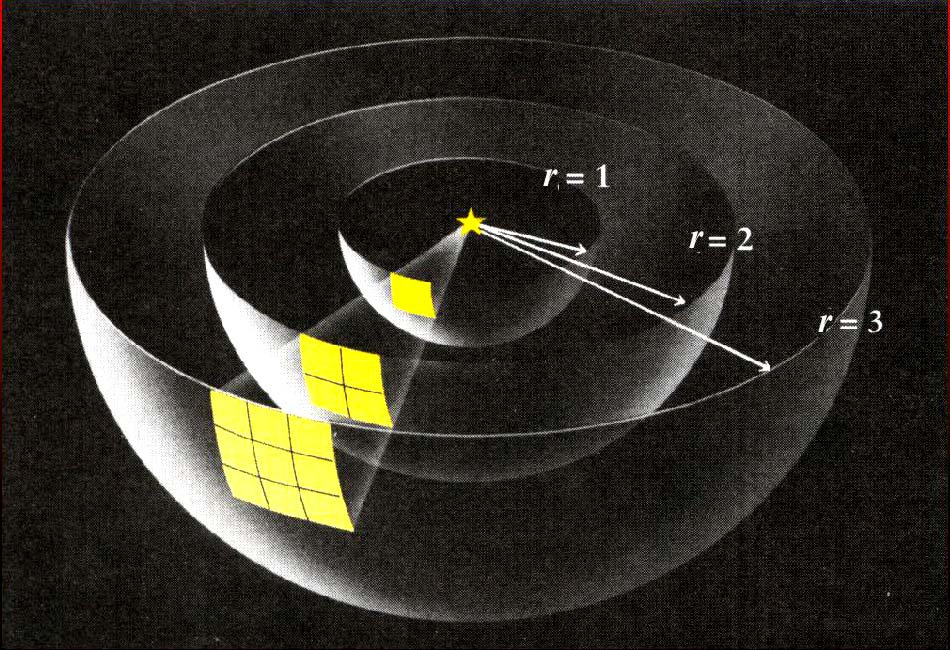

where F = number of photons produced by the source and r = object’s distance

|

This equation follows from the area of a sphere centered on

the source, |

Light is attracted by gravitational fields.

| According to Einstein's theory of relativity, light is attracted by

gravitational fields. This effect was originally confirmed by observing the apparent shift

in the positions of stars as their light grazed the limb of the sun, but is now observed

in many other situations. |

|

|

What are the key aspects of electromagnetic radiation![]()

|

Rainbow, from http://www.lioncrusher.com/ecard/ |

|

Click to return to syllabus |

||

| Click to return to Physical Laws | hypertext |

Click to go to Spectroscopy |