|

Galileo lived at about the same time as Kepler (they did their most important work

around 1600-1610) and exchanged letters with him. He made a number of fundamental contributions to our understanding

of the solar system and the laws of physics. See

http://es.rice.edu/ES/humsoc/Galileo/. |

Key points: Importance of doing

experiments; birth of modern physics and how it differed from medieval physics;

discoveries of moons of Jupiter, phases of Venus and impact on solar system theories

| He introduced the idea of making

measurements or experiments to understand how things happen. |

Pure logical thinking cannot yield us any knowledge of the

empirical world; all knowledge of reality starts from experience and ends in it...Galileo

saw this, and particularly because he drummed it into the scientific world, he is the

father of modern physics - indeed, of modern science altogether. -- Albert

Einstein |

| Galileo's greatest contribution to physics

(after the notion of doing experiments at all) was his studies of the motions of objects. He rolled balls down this inclined plane |

and arranged bells so they would ring as the balls passed. By

adjusting the positions of the bells, he could compare with time standards (perhaps his

singing!). The inclined plane slowed down the "falling" of the objects so he

could study it (Pictures from Museum of Science, Florence).

|

|

|

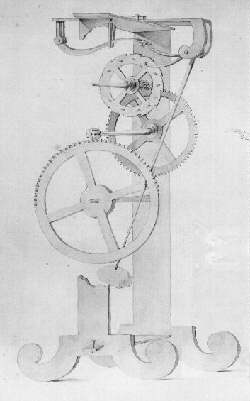

He also recognized the value of the pendulum for accurate time keeping Pendulum clocks set the standard for accuracy for

centuries.

Pendulum clocks set the standard for accuracy for

centuries.

He developed the concept of inertia: if an object is at rest, it will stay at rest unless something

acts upon it to move it. Similarly, if an object is moving in a straight line at constant

speed, it will continue to do so unless something acts upon it.

This realization had escaped people because friction is so prevalent and

it provides a force that usually causes moving objects to slow down.

- he discovered that the Milky Way is comprised of

stars

- he discovered sunspots

- he discovered craters, mountains, and valleys on the

Moon (Picture from Scientific American)

|

|

These observations (stars in the Milky Way, geologic structures on the

Moon, sunspots) don’t provide any test for or against the Copernican model of the

solar system. However, sunspots, for example, do provide

evidence that the heavens are not perfect and unchanging as described by Aristotle,

Ptolemy, and other ancients.

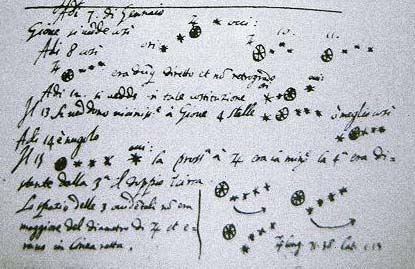

- - he discovered the four

largest moons of Jupiter (now called the Galilean satellites in his honor)

(From R. Baalke, http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/galileo/ganymede/discovery.html)

The moons that Galileo observed orbiting Jupiter again did not prove the

Copernican concept, but they appeared to support it indirectly. They proved that not

everything orbits the Earth. Furthermore, Jupiter and its moons actually look like a

miniature solar system in many respects. The fact that Jupiter can move through space and

not leave its moons behind supports the concept that the Earth can move without leaving

its moon behind.

|

|

| The phases of Venus were

a convincing demonstration of the heliocentric solar system, or at least that Venus comes

between the earth and sun as it predicted (and contrary to the Ptolemaic system).

They result from its position in the solar system between us and the sun. Mercury also

exhibits phases but it’s much harder to observe than Venus. The Ptolemaic system

could explain only some of the phases exhibited by Venus. |

|

| In the Ptolemaic system (left), Venus always lies between the sun

and the earth and it would always show a crescent phase. The Copernican system (right)

predicts a full range of phases for Venus as it passes from between the sun and the earth

to being on the opposite side of the sun from the earth. (from Parvis

Ansari http://artsci.shu.edu/physics/1007/historylv.html) |

From Scott

Anderson, copyright open course, http://www.opencourse.info/ From Scott

Anderson, copyright open course, http://www.opencourse.info/ |

Watch in the animation as Venus (the magenta dot in the right panel)

comes around the sun and goes between it and the earth. |

The combination of Kepler’s Laws and

Galileo’s observations provided the death knell for the Ptolemaic System. Galileo realized this, but his

over-zealous promotion of it led to the famous conflict with the Catholic Church

Galileo’s law of inertia provided some hints about how the planets

must move:

1) if there is no friction in space, then

planets would be able to move forever without changing their paths or losing their energy

of motion

2) since planets move in curved paths rather

than straight lines, there must be some force acting on them to change direction

But Galileo was not able to put the above facts together with

Kepler’s Laws to come up with the final explanation of why the planets move as they

do.

From Scott

Anderson, copyright open course,

From Scott

Anderson, copyright open course,