Kenji Miyazawa was a

Japanese astronomer and poet. His most famous work is "Night on the Milky Way

Train", that starts almost as if it took place in NatSci 102:

Kenji Miyazawa was a

Japanese astronomer and poet. His most famous work is "Night on the Milky Way

Train", that starts almost as if it took place in NatSci 102: Kenji Miyazawa was a

Japanese astronomer and poet. His most famous work is "Night on the Milky Way

Train", that starts almost as if it took place in NatSci 102:

Kenji Miyazawa was a

Japanese astronomer and poet. His most famous work is "Night on the Milky Way

Train", that starts almost as if it took place in NatSci 102:

"So you see, boys and girls, that is why some have called it a river,

while others see a giant trace left by a stream of milk. But does anyone know what really

makes up this hazy-white region in the sky?'

The teacher pointed up and down the smoky white zone of the Milky Way that ran across a

huge black starmap suspended from the top of the blackboard. He was asking everybody in

the class.

Campanella raised his hand, and at that, four or five others also volunteered. Giovanni

was about to raise his hand, but suddenly changed his mind.

Giovanni was almost sure that it was all just made up of stars. He had read that in a

magazine. But lately Giovanni was sleepy in class nearly every day, had no time to read

books and no books to read, and felt, for some reason, that he couldn't properly follow

anything anymore."

To find the rest, link to http://hina.tudza.com/,

click on the link to "Night on the Milky Way Train", or just follow this link ![]()

Here is an article on Kenji Miyazawa:

The Milky Way Train: Celebrating Kenji Miyazawa

By: Steve Renshaw and Saori Ihara

Revised November, 1999

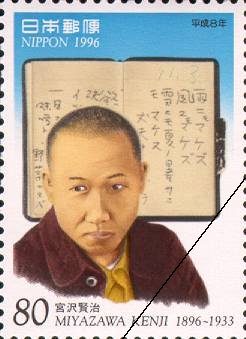

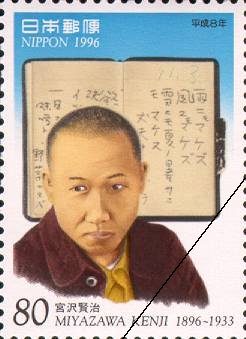

1996 marked the 100th anniversary year of the birth of Kenji Miyazawa... poet, novelist,

and amateur astronomer who lived in Japan in the early 20th century.While Miyazawa died at

the untimely age of 37, his work had a significant impact on Japanese literature. The

January 1996 issue of Tenmon Guide (Astronomy Guide) highlighted the life of this writer

whose works are still affectionately read in modern Japan.

Having such a strong interest in astronomy, Miyazawa often sought to weave astronomical

phenomena into his stories. One of his most famous works is titled "The Night of the

Milky Way Train" (a translation published by Stone Bridge Press is available from

WeatherHill). Written not too long after the late 19th century Meiji restoration, this

work represents what we often see as the paradox of Japanese culture and virtue played

against a Westernized backdrop. The story remains, for many young Japanese, their first

association with the wonder of the "starry sky". Here is a brief synopsis of the

story...

Miyazawa's mix of East and West begins with the names of the two young characters of the

story: Jovanni (Giovanni) and Kanpanera (Campanella). The story takes place during the

imaginary "Centaurus" Festival, a time when lanterns are lit to show deceased

ancestors the way home. This imaginary festival occurs in August, and in the story,

Miyazawa images children running and scampering, yelling that Centaurus is "dropping

dew" [no doubt, a somewhat misplaced reference to the Perseids].

On the night of the festival, Jovanni is sent to the store to get some milk. On the way,

he stops on a hill to lay and gaze at the stars. He hears a voice that sounds like a train

conductor saying "Milky Way Station!" and suddenly finds himself with a seat on

"The Milky Way Train". Across from him sits his friend, Kanpanera. Thus, a

journey starts for the boys on a trip around the Milky Way.

Miyazawa highlights many experiences for Jovanni and Kanpanera, carefully weaving

phenomena with fantasy. One of the first stops for the youths is at "Hakuchou

Station" (Swan... Cygnus) where the boys see an image of a cross made by "the

frozen north cloud". Here they also see a "beach" over 500 million years

old where a paleontologist is digging the fossil of the ancient ancestor of a cow [note

Miyazawa's poetic use of stellar distance and time and the ever present "milk"

related images]. Some experiences involve phenomena not readily seen with the naked eye.

For example, our travelers pass the observatory at Albireo, where the blue and gold

markers measure the flow of the Milky Way river. One "stop" references the

galactic center; just south of Washi Station (Eagle... Aquila) the river divides, and on

the "sand bar", a signalman is lighting lanterns [referring to the bright region

of Sagittarius] as a warning that swans, eagles, peacocks, and crows may be crossing.

The story continues with a number of experiences and brilliant images as the journey

traverses the Summer Milky Way. One especially poignant "stop" on the route

seems to relate to traditional Japanese values stemming from the still ever present Edo

era. At Scorpio, the bright light from Sagittarius makes trees cast shadows, and there is

something that shines clear and red like a ruby [Antares]. Miyazawa relates Jovanni's

sense of this, and it becomes even more significant at the end of the story. For Jovanni,

this star symbolizes the responsibility one has to others and the sacrifice that one is

willing to make in order to help ones friends, even to the point of dying (shedding

blood). He also notices the "accompanying" stars [probably Nu and Omega Sco] and

is reminded of a very ancient Japanese association with these stars... the importance and

closeness of friendship.

At journey's end, the train makes its final stop at the Southern Cross. Jovanni looks

around and notices that Kanpanera has disappeared. He suddenly awakes and finds himself on

the hill near his home. As he continues into town on his errand, he sadly learns that his

friend Kanpanera has actually drowned earlier in the evening while trying to save friends

swimming in a nearby river.

There were several editions of Miyazawa's story. In the first, the journey continued

around the whole galaxy. The final edition (above) obviously concentrates on the Summer

Milky Way. My synopsis does not do justice to the subtlety and beauty of Miyazawa's poetic

style. Still, I hope list members find it interesting. This story, loved and admired

throughout Japan, is both charming and innocent. At the same time, its bittersweet end

(especially for children) may seem strange to Western ears. Yet, it is just this

highlighted virtue of self-sacrifice that defines so much of the traditional Japanese view

of responsibility to others and forms the basis for what some might mistakenly interpret

as a fatalistic spirit. Sadly, Miyazawa's own younger sister died two years before he

began writing this story, and many believe that this formed the basis not only for the

ending, but also the emphasis on "relationship".

Many amateur and professional astronomers in Japan were inspired as youths by this story,

and it seems to have become a permanent part of modern Japanese Starlore. "The Night

of the Milky Way Train" continues to inspire children and adults to gaze in wonder at

the heavens; many may be the astronomers and comet hunters of the future. Miyazawa loved

the starry sky and spent many nights drinking in its wonder and many days studying its

design. More than a hundred years after his birth, the legacy of this amateur astronomer

continues to live.

from http://www2.gol.com/users/stever/kenji.htm