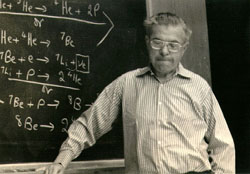

Fred Hoyle, Cosmologist and Crank

What made Fred Hoyle such a fascinating figure in big-time cosmology was that he

combined the accomplishments and understandings of the century’s elite – think

Einstein, Bohr, Feynman – with proposals associated with cranks. In mainstream

science, he helped construct one set of theories that looks spectacularly right, and

another set that looks just as spectacularly wrong. As an apparent member of the lunatic

fringe, he talked about an alien consciousness that ran the earth, diseases from space,

and panspermia (his intriguing proposal that interstellar space dust is composed largely

of bacteria.) His career raises interesting questions about the role of orthodoxy in the

sciences, especially cosmology, where answers are necessarily provisional.

Hoyle’s biggest contribution to orthodox cosmology was

nucleosynthesis – the process by which elements heavier than hydrogen are created

within both stars and exploding stars, or supernovas. In a classic paper from 1957, Hoyle,

along with three other scientists, showed how stars, in their spectacular death throes

culminating in supernova explosions, create heavier elements that are then blown out into

the universe. The planets in our solar system, many rich in elements heavier than

hydrogen, are aggregated remnants of stars that exploded billions of years ago.

Hoyle’s biggest contribution to orthodox cosmology was

nucleosynthesis – the process by which elements heavier than hydrogen are created

within both stars and exploding stars, or supernovas. In a classic paper from 1957, Hoyle,

along with three other scientists, showed how stars, in their spectacular death throes

culminating in supernova explosions, create heavier elements that are then blown out into

the universe. The planets in our solar system, many rich in elements heavier than

hydrogen, are aggregated remnants of stars that exploded billions of years ago.

In the late 30s, no one knew just how elements heavier than hydrogen were created.

Prevailing wisdom held that the sun was composed mainly of iron. By 1960 it was widely

accepted that the sun (and all other stars) was mostly hydrogen, and that heavier elements

were produced by the nucleosynthetic processes that Hoyle’s team had postulated.

Though the work garnered a Nobel Prize for one of the paper’s authors, William

Fowler, in 1983, Hoyle and the two other collaborators were somehow overlooked by the

committee.

Hoyle’s biggest mistake, so far as orthodox science is concerned, was his

conception of the Steady State Universe, first proposed in 1948. The current consensus

holds that the Universe was created in an explosion now popularly known as the Big Bang.

Hoyle envisioned instead an expanding universe in which matter was spontaneously created

in gaps between galaxies. There was no explosion. Hoyle’s Steady State Universe was

perhaps infinitely old – at any rate at least 800 billion years old, as opposed to

10-20 billion for the Big Bang. The theory was a worthy adversary of Big Bang until the

mid-60s. Then it was dealt a ringing blow by the discovery of cosmic background radiation,

predicted by Big Bang but unaccounted for by Steady State. Hoyle never ceased to tinker

with his theory, eventually accounting for background radiation within its parameters, but

it was too late; barely anyone takes it seriously today. In his memoirs, Hoyle was

philosophical in defeat: “The Universe eventually has its way over the prejudices of

men, and I optimistically think it will do so again.”

Hoyle cast his net widely. While simultaneously devising the idea of nucleosynthesis

and defending the Steady State, he was developing a new theory of gravity (which went

nowhere), giving talks on the BBC (in which he derisively coined the phrase “Big

Bang”), scaling all 280 peaks over 3000 feet in Scotland, and writing science

fiction. GoodBye! decided to take one for the team, and actually read one of his

novels, October the First Is Too Late, from 1966. Because it would be irritating to

find a single person who did everything well, it comes as great comfort to report that

this book sucks. The protagonist, a composer of “modern music,” is cast into a

world in which Hawaii and Great Britain exist in 1966, while all of the Americas are in

the 18th century, Greece is still in the classical period, and Russia is so far in the

future that it is covered by a great glass dome. Since the protagonist knows nothing of

physics, a physicist sidekick soliloquizes until the plot is comprehensible. The

protagonist sails to classical Greece, towing a grand piano, and fights a musical duel

with a priestess who … enough. Suffice it to say that Hoyle’s hero manages

coitus with women of classical Greece, modern California, and Futureworld, without

sounding the least note of passion. The book’s theme is an exploration of quantum

time and the many-worlds hypothesis – the idea that in every quantum event two

universes are created, each spinning off to its own unique future. Scintillating it is

not. [Instructor's note: Hoyle's science fiction is very uneven. His first effort,

"The Black Cloud," has an original and interesting premise and is well written.

It is recommended as interesting reading that will give a new insight to the breadth of

forms that alien life might assume.]

In 1958, Hoyle was appointed to the Plumian Professorship at Cambridge, the

realm’s highest post in astrophysics. He had recently published his groundbreaking

paper on nucleosynthesis. He was well-known to the public for his BBC radio lectures, and

for his first science fiction novel, The Black Cloud, which soon became a TV show as well.

So how did it happen that by 1974, he had been knighted and yet was completely

marginalized within science? It’s hard to say exactly, but it may have been committee

work.

His memoir, Home is Where the Wind

Blows (1994) is wonderfully evocative of the English society of Hoyle’s boyhood,

when he forced his family to allow him to school himself, and used his learning in

chemistry to blow things up. The book is full of fascinating ferment through the 40s and

50s, when his contributions to radar were important to the war effort, and his

contributions to physics were seminal. But by the 60s his reminiscences become nearly

unreadable as one committee blends into the next and political infighting among

cosmologists apparently causes him to become unhinged.

His memoir, Home is Where the Wind

Blows (1994) is wonderfully evocative of the English society of Hoyle’s boyhood,

when he forced his family to allow him to school himself, and used his learning in

chemistry to blow things up. The book is full of fascinating ferment through the 40s and

50s, when his contributions to radar were important to the war effort, and his

contributions to physics were seminal. But by the 60s his reminiscences become nearly

unreadable as one committee blends into the next and political infighting among

cosmologists apparently causes him to become unhinged.

Hoyle earnestly fought with his nemesis, the astronomer Martin Ryle of Oxford, over any

number of issues. In the memoir, this conflict caused the usually-temperate Hoyle to

explode in an attack on the discipline of astronomy for its adherence to what he called

the “principle of maximum trivialization,” its tendency “when two

alternatives are available, [to] choose the more trivial.” Conflict and resentment

between the two were personal as well as professional; when Ryle was awarded the Nobel in

1974, Hoyle went public with his accusation that Ryle’s research had actually been

done by a woman, a junior scientist on Ryle’s team. This imbroglio is posited by some

as the reason Hoyle did not share in the 1983 Nobel. Though Hoyle was knighted in 1972 for

contributions to astrophysics, in 1973 he resigned his professorship over a series of

committee problems. From that time on his ideas were devalued and his dogged devotion to

Steady State prompted his reputation as a crank. Rather than retreat, he began to

promulgate a series of ideas which the mainstream scientific community regarded as

idiosyncratic at best.

***

The ideas at the core of cosmology are, for humans on Planet Earth, absurd: the Big

Bang, quantum theory, black holes, the size and age of the universe. Cosmologists

basically take ideas derived from mathematics and attempt to cast them on to the entire

universe – and they have an incredible record of success in predicting subsequent

observations. It is not too much to say that theirs is the pinnacle of human rationality

in terms of understanding the observable universe, from the tiniest particles to the most

gigantic structures of intergalactic space.

But events at the Big Bang and at the origin of life cannot be tested in the same sense

as a chemical reaction; they are unique. Therefore much of what scientists believe to be

true about the history of the universe is conjectural, yet predictions can be made.

Physicists are constantly coming up with bizarre ideas that are shot down by colleagues,

no harm there. But when Hoyle went solo after resigning from Cambridge there was no longer

any check on him. His reputation allowed him to publish whatever he wanted. Soon he was

coming up with really strange stuff. The interstellar dark matter was, he said, composed

in part of bacteria. Since bacteria permeated the Universe, it seeded life everywhere,

what Hoyle called “panspermia.” The chances of life appearing spontaneously on

Earth were vanishingly low: according to Hoyle, one in 1040000. (In

Hoyle’s defense, it must be said that there is no really convincing account of the

origin of life on Earth.) This theory was in line with his well-accepted work on

nucleogenesis. If all the heavier elements were the product of supernova dispersion, why

not life itself?

But even if Hoyle could produce tantalizing spectrum evidence that bacteria existed in

space, his theories got much weirder. He theorized that not only the origin of life, but

evolution was also too complex to have occurred by chance: an evolved alien consciousness

must have directed it. Diseases such as BSE, influenza, and polio were the result of

comets or sunspots that caused interstellar particles to fall to earth. Worse: he declared

that bumblebees were well fitted for interstellar space travel. In a supremely silly

moment he published a book claiming that the classic archaeopteryx fossil was a hoax

– this despite having no professional credential in paleontology.

His memoirs record a tea party in Princeton in 1953, where he met Immanuel Velikovsky,

perhaps the 20th century’s premier scientific crank. Hoyle gently told Velikovsky

that his work was not properly scientific. “This made Velikovsky look sad, which is

how we parted.” Hoyle must have felt the irony. By the time his memoirs appeared, his

own favorite ideas were as out of favor as Velikovsky’s. But he did not remark on the

matter.

Hoyle’s failures should not be damning, for he was a man who followed ideas

wherever they led him. He wrote that ideas were like catching a bird that has flown into

your house. “The transformation from wild terror to calmness seems entirely magical

… the bird watches you with a bright eye … you throw up your arms and release

the bird, and away it soars. I feel it should be like that with ideas.” He said that

much theorizing in physics was about style and described his own style as

“ruthless.”

Some of his contrarian work was useful. His tweaks to the Steady State theory forced

Big Bang believers to come up with better evidence, and his fundamental attack on the Big

Bang is succinct: “Big-Bang cosmology is an illusion because, after asserting that

matter cannot be created, it proceeds to create the entire Universe. It does so outside of

both mathematics and physics, by metaphysical assertion.” The “theory,” he

said, “is really a catalogue of hypotheses, like a gardener’s catalogue.”

Together with Hoyle, we may find it disturbing that scientific orthodoxy is so firmly

rooted around a single, quite unprovable, hypothesis.

Hoyle continued to seek mainstream scientific approval and was widely respected despite

his quirks. His memoirs omit Nobels, his knighthood, science fiction, or, for that matter,

panspermia or bumblebees. Last year he published a book with more evidence for the Steady

State theory titled A Different Approach to Cosmology. Unsurprisingly, it was not

well-received, although Scientific American said, “it’s heterodoxy is

seductive.”

The heroes of 20th century cosmology have all had their quirks. Einstein famously

rejected quantum theory. Feynman was a wild man. Stephen Hawking recently recommended that

human genetic engineering should proceed because otherwise robots may take over the world.

Of one thing we may be certain: the Universe is much stranger than the quirks of the

cosmologists who attempt to explain it.

Hoyle was 86 when he died. He continued to hike in the mountains and

theorize to the end.

http://www.goodbyemag.com/jul01/hoyle.html

Hoyle’s biggest contribution to orthodox cosmology was

nucleosynthesis – the process by which elements heavier than hydrogen are created

within both stars and exploding stars, or supernovas. In a classic paper from 1957, Hoyle,

along with three other scientists, showed how stars, in their spectacular death throes

culminating in supernova explosions, create heavier elements that are then blown out into

the universe. The planets in our solar system, many rich in elements heavier than

hydrogen, are aggregated remnants of stars that exploded billions of years ago.

Hoyle’s biggest contribution to orthodox cosmology was

nucleosynthesis – the process by which elements heavier than hydrogen are created

within both stars and exploding stars, or supernovas. In a classic paper from 1957, Hoyle,

along with three other scientists, showed how stars, in their spectacular death throes

culminating in supernova explosions, create heavier elements that are then blown out into

the universe. The planets in our solar system, many rich in elements heavier than

hydrogen, are aggregated remnants of stars that exploded billions of years ago.  His memoir, Home is Where the Wind

Blows (1994) is wonderfully evocative of the English society of Hoyle’s boyhood,

when he forced his family to allow him to school himself, and used his learning in

chemistry to blow things up. The book is full of fascinating ferment through the 40s and

50s, when his contributions to radar were important to the war effort, and his

contributions to physics were seminal. But by the 60s his reminiscences become nearly

unreadable as one committee blends into the next and political infighting among

cosmologists apparently causes him to become unhinged.

His memoir, Home is Where the Wind

Blows (1994) is wonderfully evocative of the English society of Hoyle’s boyhood,

when he forced his family to allow him to school himself, and used his learning in

chemistry to blow things up. The book is full of fascinating ferment through the 40s and

50s, when his contributions to radar were important to the war effort, and his

contributions to physics were seminal. But by the 60s his reminiscences become nearly

unreadable as one committee blends into the next and political infighting among

cosmologists apparently causes him to become unhinged.