Cartoon from Sidney Harris, "Einstein Simplified"

There is no way to describe scientifically the origin of the universe without treading upon territory held for millennia to be sacred. Beliefs about the origin of the universe are at the root of our consciousness as human beings. This is a place where science, willingly or unwillingly, encounters concerns traditionally associated with a spiritual dimension.

For thousands of years people have wondered, speculated, and argued about the origin of the universe without actually knowing anything about it. In the closing years of the twentieth century, we're learning enough to begin to peer across the gulf that separates our universe from its source at the beginning of -- or perhaps before -- the Big Bang. A story is emerging in modern cosmology that will, if it follows the pattern of earlier shifts in cosmology, change our culture in ways no one can yet predict...

Why is this important? In a speech given in July 1994... the Czech poet-president Vaclav Havel said that the planet is in transition. As vastly different cultures collide, all consistent value systems are collapsing. We cannot foresee the results. Science, which has been the bedrock of industrial civilization for so long, he said, "fails to connect with the most intrinsic nature of reality and with natural human experience. It is now more a source of disintegration and doubt than a source of integration and meaning.... We may know immeasurably more about the universe than our ancestors did, and yet it increasingly seems they knew something more essential about it than we do, something that escapes us.... Paradoxically, inspiration for the renewal of this lost integrity can once again be found in science...a science producing ideas that in a certain sense allow it to transcend its own limits.... Transcendence is the only real alternative to extinction." [1]

Modern cosmology is now undergoing a foundation-building revolution as it seeks a verifiable description of the nature and origin of the universe. This revolution may require that we transcend previous notions of space, time, and even reality. This seems to me the kind of science Havel is hoping for-a science whose metaphors may illuminate not only the subject matter of its own field but possibly also problems of humanity and the earth from a cosmic perspective... How well our cosmology is interpreted in language meaningful to ordinary people will determine how well its elemental stories are understood, which may in turn affect how positive the consequences for society turn out to be...

Anthropologists tell us that in virtually all traditional cultures, a cosmology is what gives its members their fundamental sense of where they come from, who they are, and what their personal role in life's larger picture might be. Cosmology is whatever picture of the universe a culture agrees on. Together with the picture -- upholding the picture -- is a story that is understood to explain the sacred relationship between the way the world is and the way human beings should behave. Other cultures' stories may not have been correct by modern scientific standards, but they were valid by their own standards, and they had the power to ground people's codes of behavior and their sense of identity within a larger picture. This sense of identity may be part of what Havel feels has been lost.

If you ask a modern audience of people fascinated by cosmology but untrained in it to close their eyes and visualize the universe, some will report seeing endless space with stars scattered unimaginably far apart, others will see great spiral galaxies, and others will see an exotic scene such as the rising of an ember-red moon over an unknown planet. They do not realize that these are merely snapshots on a given scale of the universe -- no more representative of the universe as a whole than is a single molecule of DNA or a moonrise over your own backyard. The strange fact is that in modern Western culture people have only the foggiest idea how to picture the universe, and certainly no consensus on it.

The lack of social consensus on cosmology in the modern world has caused many people to close off their thinking to large issues and long time scales, so that small matters dominate their consciousness. Of course, modern people do know much more about many things than members of isolated, traditional cultures, but we are not so different in our basic needs from people millennia ago. We have to get our sense of context somewhere. It is worth looking at earlier cosmologies and the cultures in which they held sway to understand how deep and in fact inextricable the connection is.

In Biblical times when people looked up at a clear, blue sky, they saw a transparent dome that covered the entire flat earth [2]. It was an awesome object, created by God himself on the second day to hold back the endless quantities of blue water clearly visible above it. There was water above and water beyond the horizon; doubtless there was also water below. God had divided the waters "above" from the waters "below" by constructing this immense dome that held open the space for dry land. In the Hebrew Bible the dome is called "raqi'a," meaning a firm substance, and rendered in the King James translation as "the firmament" -- a concept that cannot be understood independently of the flat earth cosmology in which it made sense. The firmament in Biblical times was understood to be firm only by the will of God. If God were angered, as everyone believed had actually happened in the time of Noah, "the windows of heaven" and "the fountains of the deep" could burst open once again and those lovely blue waters would destroy the earth. God was said to have promised not to do it a second time and to have sealed this covenant with the rainbow, but who could predict the behavior of God? A watery Sword of Damocles hung over every creature on the flat earth, and God held the threads.

|

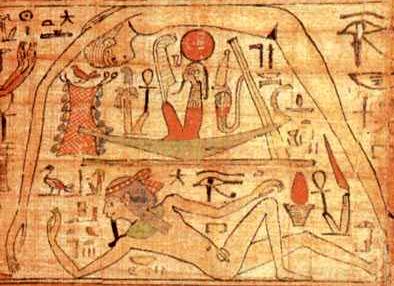

In ancient Egypt the dome of the sky was represented by the goddess Nut, who arched her back over the earth so that only her hands and feet touched the ground. She was the night sky, and the sun, the god Ra, was born from her every morning [3]. |

NUT, from http://www.louisville.edu/~aoclar01/ancient/astronomy/egypt-cosmos.htm |

At more or less the same time that the Hebrew Bible as we know it was being compiled -- about the 5th century BCE-Greek philosophers lived in a different universe. Their earth was not flat and domed but a round celestial object. Aristotle honed the picture so that the lunar sphere -- a sphere the size of the orbit of the moon -- was defined as the border between the earthly world of change and decay inside and the perfect, unchanging heavens outside.

With modifications by the 2d century CE Alexandrian astronomer Ptolemy, who added details to account for careful astronomical observations, Aristotle's image of concentric spheres, and not the Bible's flat domed earth, had become by the Middle Ages the universe for Jews, Moslems, and Christians alike.

|

Thus on a clear night in Medieval Europe, a person looking up into the cathedral of the sky would have seen huge, transparent spheres nested inside each other, encircling the center of the universe, the earth [4]. In an uneasy alliance with Christian theology the planets were still identified with the Ancient Roman gods Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, and were still believed by many to be divine enough to influence people's lives. Immediately outside the sphere of the fixed stars lay Heaven. This was the monotheistic compromise with Aristotle and Ptolemy. God was physically right out there. Everything between heaven and earth had its eternal place, chosen by God. |

| From Dante's (1265-1321) "The Divine Comedy,"from H. & A. Mathai, UN/ESA http://www.seas.columbia.edu/~ah297/un-esa/universe/universe-chapter2.html) | |

|

A worm in the soil, the lowliest serf, and the king himself had been placed by God exactly where they belonged in the great chain of being, and there was no questioning the divine hierarchy. The hierarchies of church, nobility, and the family were divinely sanctioned -- they mirrored the cosmos itself. |

| From "The Garden of Earthly Delight, by Hiernymous Bosch, 1504," see Chaisson and McMillan, http://cwx.prenhall.com/bookbind/pubbooks/chaissonat4/chapter2/deluxe.html |

We may scoff that they saw such a cosmos, but not that they took the cosmos as the sacred model for society. They understood that humans can only be content by seeking to be in harmony with the universe.This is a lesson our culture could do well to learn.

A new cosmology is subversive in the deepest sense of the word. The stable center was torn out of the Medieval universe at the beginning of the 17th century, when Galileo's observations showed that the Aristotelian-Ptolemaic earth-centered picture was wrong, and Kepler's geometric interpretations of Tycho Brahe's data were built upon the sun-centered model that Copernicus had put forward more than sixty years earlier [5]. Europe's conceptual universe was shaken. Like unreinforced buildings in an earthquake, the power structures of society were irreparably cracked and undermined, and this was soon obvious to all thinking people. As John Donne wrote in 1611 upon learning about Galileo's telescopic observations:

The new Philosophy calls all in doubt,

The Element of fire is quite put out;

The Sun is lost, and th'earth, and no man's wit

Can well direct him where to look for it...

'Tis all in pieces, all coherence gone;

All just supply, and all Relation;

Prince, Subject, Father, Son, are things forgot... [6]

..Eventually, following the lead of Bacon and Descartes, science protected itself by entering into a de facto pact of noninterference with religion: science would restrict its authority to the material world, and religion would hold unchallenged authority over matters of human meaning and the spirit. By the time Isaac Newton was born in 1642, the year of Galileo's death, the spoils of reality had been divided. The physical world and the world of human meaning were now two separate universes...For more than 300 years, since the time of Isaac Newton, science has been understood by most educated people to imply an image of the universe as infinite, or at least incomprehensibly vast, almost empty space, with stars scattered at great distances from each other but no center, no purpose, no location for God, and no obvious implications for human behavior. Blaise Pascal wrote, "engulfed in the infinite immensity of spaces whereof I know nothing and which know nothing of me, I am terrified.... The eternal silence of these infinite spaces alarms me."[7] With an image of a cold universe in which humans play no necessary role whatsoever, and no serious explanation of how things got this way, a society suffers from a kind of rootlessness that prevents a sense of connection with the universe.

...Scientific cosmology today has entered a golden age of discovery because of a combination of extraordinary new instruments and telescopes on the one hand and daring theoretical breakthroughs on the other. Data is flooding in, and cosmological theories are being honed to levels of precision unimaginable even a generation ago. We may see in the first decades of the 21st century the emergence of a new universe picture that can be globally acceptable, and with this and the contributions of image-making writers, artists, and spiritual visionaries, it is possible that the painful centuries-long hiatus in human connection with the universe will end... This universe could become the most inspiring source of new ways of interpreting and addressing the problems of our planet...

I will present one possible example of a way of looking at the universe that is consistent, as far as it goes, with what we understand of the universe today yet is simple, graphic, highly suggestive, and carries the mythic undertones essential to an appreciation of the power of a cosmology....

[The universe] cannot be pictured the way a galaxy, for example, can be pictured in a photograph or painting for at least three reasons: First, a photograph is of something outside the eye, and the universe is not outside us, and we are never outside it. We are it on our scale. Second, a photograph captures a moment in time, but the universe encompasses time itself and no slice of time can even suggest that. And third, the universe cannot be imagined as a picture because it's almost all invisible dark matter. Moreover, all the radiation in the universe is also invisible to us, except for the tiny band of frequencies between red and blue. It is essential to give up trying to imagine the universe through the eyes, yet people need something visual.

The best solution I have found is to represent the universe using one of the oldest symbols for it known to humankind, a symbol found in countless cultures around the globe. It is the snake swallowing its tail -- an "uroboros" as the Greeks called it. Earlier peoples used it to represent eternal life, partly because snakes were often believed to live forever, since the sloughing of their skin was seen as a rebirth; and partly because the circle of its body was a cycle without end. The uroboros had different meanings in different cultures, but it tended to represent whatever was seen as fundamental in a culture. Now it might carry a new interpretation.

From the Planck scale to the cosmic horizon, the visible universe encompasses about 60 orders of magnitude. The size scales of the universe can thus be arrayed around the serpent like minutes around the face of a clock. Sheldon Glashow originally suggested this symbol, with the swallowing of the tail expressing his hope for a unification of the theories governing the largest and smallest scales [8]. I noticed [9] that there are many connections across the diagram: electromagnetism dominates the bottom; the strong and weak interactions not only dominate on nuclear scales but also describe energy generation in stars and determine the composition of planetary systems; and dark matter, which is gravitationally dominant on galactic and larger scales, may be associated with the physics of still smaller scales.

The Cosmic Uroboros represents the universe as a continuity

of vastly different size scales, of which the largest and smallest may be linked by

gravity. Sixty orders of magnitude separate the very smallest from the very largest.

Traveling around the serpent from head to tail, we move from the scale of the cosmic

horizon to that of a galaxy supercluster, a single galaxy, the solar system, the sun, the

moon, a mountain, a human, a single-celled creature, a strand of DNA, an atom, a nucleus,

the scale of the weak interactions, and approaching the tail the extremely small size

scales on which physicists hope to find evidence for Supersymmetry (SUSY), dark matter

particles such as the axion, and a Grand Unified Theory. There are other connections

between large and small: electromagnetic forces are most important from the scale of atoms

to that of mountains; strong and weak forces govern both atomic nuclei and stars; cosmic

inflation may have created the large-scale of the universe out of quantum-scale

fluctuations.

The Cosmic Uroboros represents the universe as a continuity

of vastly different size scales, of which the largest and smallest may be linked by

gravity. Sixty orders of magnitude separate the very smallest from the very largest.

Traveling around the serpent from head to tail, we move from the scale of the cosmic

horizon to that of a galaxy supercluster, a single galaxy, the solar system, the sun, the

moon, a mountain, a human, a single-celled creature, a strand of DNA, an atom, a nucleus,

the scale of the weak interactions, and approaching the tail the extremely small size

scales on which physicists hope to find evidence for Supersymmetry (SUSY), dark matter

particles such as the axion, and a Grand Unified Theory. There are other connections

between large and small: electromagnetic forces are most important from the scale of atoms

to that of mountains; strong and weak forces govern both atomic nuclei and stars; cosmic

inflation may have created the large-scale of the universe out of quantum-scale

fluctuations.

Why is this symbol useful? People asked to visualize "the universe" will far more often think of the largest thing they know of than the smallest. Few realize that the universe exists on all scales, everywhere, all the time. This is a truly extravagant thought. Largeness is by no means the most important characteristic of the universe. Focusing on it makes people feel small, not because they are, but because they are simply ignoring all scales smaller than themselves in thinking about the universe. On the Cosmic Uroboros, as I call it, if the mouth swallowing the tail is drawn at the top, humans (at one meter or so) fall more or less at the bottom -- i.e., at the center of all the size scales in the visible universe. Many students are so stunned by this apparently special place that they refuse to believe it and insist it must be a result of some tricky choice of units. I don't know if the center of the Cosmic Uroboros is in fact special, but finding themselves there certainly strikes a chord with most people. Perhaps it hearkens back to the soul-satisfying cosmology of the Middle Ages, where earth was truly the center of the universe. ...

This essay grew out of my collaboration with my wife, Nancy E. Abrams, on our course "Cosmology and Culture" and on our book in progress. I am very grateful for her help with it. See http://physics.ucsc.edu/cosmo/primack_abrams/COSMO.HTM

More on the development of ideas on cosmology at http://www.seas.columbia.edu/~ah297/un-esa/universe/index.html

1. Vaclav Havel, "The need for transcendence in the postmodern world," Futurist, v29, n4 (July-August, 1995), pp. 46ff.

2. Richard Elliott Friedman, The Disappearance of God (Little, Brown, 1995), pp. 230-235.

3. See, e.g., Jeremy Naydler, Temple of the Cosmos (Inner Traditions, 1996).

4. C. S. Lewis, "The Heavens," The Discarded Image (Cambridge University Press, 1967).

5. T. S. Kuhn, The Copernican Revolution (Vintage Books, 1959), esp. pp. 193ff.

6. John Donne's Poetry, Arthur L. Clements, ed. (W.W. Norton & Co., 1992), p. 102.

7. Blaise Pascal, Pensees, Sec. III, nos. 205-206.

8. Sheldon Glashow, sketch reproduced in T. Ferris, New York Times Magazine, Sept. 26, 1982, p. 38.

9. Joel R. Primack and George. R. Blumenthal, "What is the Dark Matter? Implications for Galaxy Formation and Particle Physics," in Formation and Evolution of Galaxies and Large Structures in the Universe, J. Audouze and J. Tran Thanh Van, eds. (Reidel, Dordrecht, 1983), pp. 163-183.

10. Joel R. Primack and Nancy Ellen Abrams, "In a Beginning…Quantum Cosmology and Kabbalah," Tikkun, v10, n1 (Jan-Feb, 1995), pp. 66-73.